Walter Wittkamp — is a committed change leader and facilitator, actively working to defend and deepen democracy

Sergej van Middendorp — is a human and organizational systems scholar/practitioner/activist supporting the generation of healthy systems

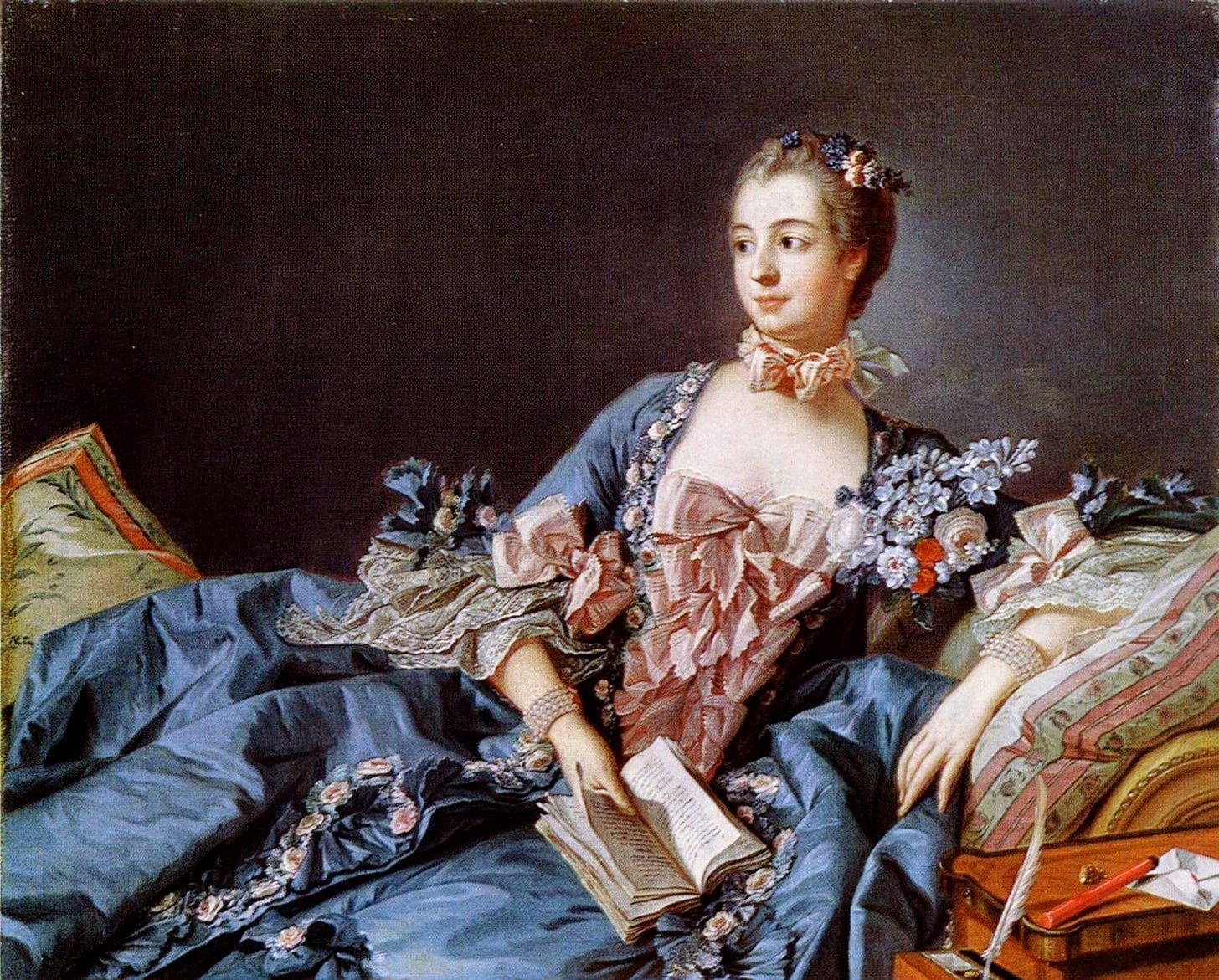

The story goes that the French king Louis XV, or his mistress Madame the Pompadour spoke about "Après nous, le déluge" ("After us, the flood”).

This statement became a metaphor for short-sighted and selfish governance: a small elite lives in luxury and doesn’t care about the consequences of their behavior for future generations. The flood refers to the total chaos that they would leave us with after their departure, but which no longer touches them personally.

Madame de Pompadour, François Boucher (1703 - 1770), Edinburgh, National Gallery

This mentality lives on in modern governance culture. Political and economic elites make decisions that maximize short-term profitability and the preservation of power, which will prove to be disastrous in the long term. Political and economic leaders continue to subsidize fossil fuels, cut down forests and destroy ecosystems, which boosts climate and ecological crises, directly threatening our livelihood. Governments and multinationals maximize economic growth and profit without taking into account social, international, intergenerational and inter-species justice. Increasingly, governments undermine democracy by concentrating power, suppressing dissent (i.e. by criminalizing the right to protest), and distributing disinformation. All in all, this leads to the erosion of the rule of law. Tech giants, complicit in this trend, profit immensely from addictive technologies and algorithm-driven manipulation – often with little regard for the societal harm they cause. This calls for urgent systems change. A livable future requires a radical re-democratization of the political system and a fundamental redesign of our democratic system.

The Polycrisis requires more democracy

We live in a time where knowledge is manipulated and disputed on a large scale, wars cause great devastation, genocide is being commited under our eyes, the biosphere is affected in a way that threatens all life and achievements in the field of social and environmental justice are reversed. These complex, interacting and inter-relating forces and the different crises that they cause are increasingly defined as the polycrisis. More and more scientists agree that the polycrisis will most likely lead to natural, economic and societal collapse [1].

Citizens should be able to trust that their government is doing everything it can to keep them safe by limiting the harm from the polycrisis by all means. The government has a constitutional duty of care to tackle problems of this magnitude. This means that the government has the responsibility to understand reality as informed by science and to do what is needed to solve the problems arising from that reality with fitting policies and measures. There is broad scientific consensus that the polycrisis requires systemic interventions in the economic, social and political fields. However, evaluations by the government’s own planning agencies on the effects of the policies currently pursued show that these are more than insufficient [2]. The government is not preventing the natural, economic and social collapse nor preparing the population for its consequences.

There are sufficient interventions to limit and partly prevent the worst consequences of the polycrisis. These options are scientifically substantiated and practically feasible. Consider, for example, the solutions proposed by Post-Growth economists [3], which envision an economic system that operates within socially just and ecologically safe limits. However, our government continues to disregard such transformative models. Political focus remains narrowly fixed on the short-term interests of coalition agreements and rooted in an almost sacred belief in endless economic growth as the foundation of all systems. By remaining within these ideological constraints, the government addresses only the symptoms of ecological, social, and economic disruption – while reinforcing the very systems that drive the polycrisis.

Rather than shifting toward sustainable foundations and regenerative goals, the existing system is merely expanded. This is difficult to change, as the status quo benefits those who already hold the most power and wealth, i.e. corporations, the affluent, and entrenched political leaders. For them, change entails uncertainty, effort, and delayed (Iower) benefits. None of which align easily with the immediate rewards of electoral politics. This creates a paradox: in attempting to respond to public dissatisfaction, politicians double down on superficial fixes, all while ignoring or denying scientific realities. The result is a growing public distrust in politics, which in turn fuels further short-termism and reactive governance. Meanwhile, the underlying polycrisis escalates exponentially, with consequences that are becoming increasingly unmanageable. The time to act is now.

19th century thinking in the 21st century

This irresponsible governance is a logical consequence of retaining the dated foundations of democracy which go back to the 19th century. As a result, our democratic system is unable to govern the big questions of our time. In fact, the way in which the system is set up accelerates the polycrisis.

The democratic systems as we know them today were largely formed in the 19th century. The core principles - sovereignty of the people, representation, the separation of powers, and individual rights - arose in the time of industrial revolution, the rise of nation states, relatively clear information exchange and short trade routes. Women’s (voting) rights were not yet actualized and secular and religious authorities kept the population small and ignorant, selective democracy (initially limited to taxpayers and later only to men) was seen as the best way to resolve social conflicts peacefully, develop economies, and distribute power more broadly. Throughout the 20th century, voting rights were extended to all adults. In the early 20th century, gradually the right to vote was extended to all adults. Social and economic changes, such as industrialization, emancipation, and the rise of labor movements, led to the formation of political parties in the early 20th century, each rooted in a clear ideology, such as socialism, liberalism, or religious beliefs. After World War II, these parties became the foundation of the representative democratic system. Their election campaigns grew increasingly professional, using marketing strategies that amplified the differences between parties. This polarization intensified as ideological distinctions faded and political parties began to converge in their social and economic positions.

On December 12th, 1917, Pieter Jelles Troelstra, Social Democratic leader at the time, announced general voting rights from the landing of The Hague city hall. Image photographic desk ”Aristo”.

The world has changed immensely compared to the times in which our democratic system was formed. Our current democracies are slow to adapt and focused on the short term while,e.g., the climate crisis requires fast and fundamental changes. The current system is built on nation states, while problems such as migration, trade and ecological collapse are cross-border and global in nature. Where 19th-century political thinkers still thought that informed citizens were the key to a healthy democracy, citizens are now flooded with disinformation, manipulated by social media algorithms and by political campaigns that play into emotions instead of being based on factual content. In the 19th century, xenophobia, racism, and misogyny were widely accepted, humanity was seen as far superior to the natural world, and there was little understanding of how our brains functioned, how the biosphere operated, or about the dangers of fossil or nuclear energy. The foundations of our democracy were established in and for a world that is vastly different from the one we live in today.

Additionally, the world order has shifted at an unprecedented pace. The geopolitical dominance of classic democratic states is crumbling while autocratic regimes are becoming increasingly assertive. Within democracies,the influence of anti-democratic forces is increasing, through the rise of populism, fascist rhetoric, disinformation, and the breakdown of societal institutions by chosen leaders. This happens not only in ‘young’ democracies such as Hungary, Turkey and India, but also in established democracies such as the United States,Italy, and arguably across the rest of the Western World too. Democratically chosen parties avoid checks and balances, disturb independent case law, hinder the free press and make science suspect.

The foundations of democracy, like rational debate, informed choice and shared values, are under pressure, also in the Netherlands. Democratic systems are being undermined by disinformation, polarization, hyper-capitalism and the dominance of technological imperialism. Problems that should themselves have been prevented by the principles of healthy democratic systems. It is becoming clear that democracies in their current form can no longer deal with the challenges of the 21st century. Because the party-political democratic system is mainly focused on power acquisition, opinion polls and established interests. Party-political democracies have become part of the problem and are increasingly in the way of good solutions.

Party politics: not for the public interest and the common good

The need for political parties to publicly amplify differences causes a fighting attitude in politics and contributes to polarization in society. Politics shifted from a focus on content to a focus on image and to non-stop campaigning, with an increasing role for media reach and framing. Policies are no longer based on long-term visions but on electoral gain and short-term popularity. With a decreasing number of members, political parties increasingly became the strongholds for professional politicians. The decision-making was shifted to party conferences, coalition talks and backrooms, so that most of the influence of ordinary citizens has disappeared. The hereditary aristocracy seems to have been replaced by an electoral aristocracy.

This gave large companies and lobbyists the chance to obtain a huge influence over policy-making, legislation and democratic decision-making. This Corporate Capture [4], strengthened by a holy belief in the ever-growing market economy as the basis of all systems, gave companies and their interests a disproportionate influence on politics and policy at the expense of the public interest and the common good. Schiphol, Shell, Tata Steel and other large polluters are causing enormous damage to human and environmental health. Damage that, according to independent reports, is often much greater than the economic benefit. Hyper Capitalism makes people lonely, depressed, overworked and addicted to consumption. But companies that benefit from all this have direct access to ministers and civil servants, so their influence outweighs those of citizens, scientists and NGOs. The Dutch government helps companies to evade taxes and, in fact, has created a business climate so that ordinary Dutch people can no longer find a home at an affordable price and get sick of air traffic noise and pollution. Many politicians and top-officials keep future career opportunities in sectors in mind that they have to regulate (or vice versa). This ensures that legislation remains mild on companies. Examples of this are former politicians and officials who switch to large consultancy firms such as McKinsey, BCG or Deloitte or to lobby clubs such as VNO-NCW, the employers association. New laws are often designed with input from lobbyists, which makes regulation beneficial to large companies. For example, the agricultural lobby has been able to influence environmental rulemaking about nitrogen for years to delay stricter regulation. In addition, companies use the media and fund research institutions to present certain policy choices as 'inevitable', ‘pragmatic’, or 'logical'. This kind of framing not only manipulates public opinion but also influences politicians (who should know better). Think of oil companies that have been sowing doubts about climate impacts, tech companies who claim that stricter privacy rules inhibit innovation and online gambling companies that say they are combating gambling addiction. In addition to this type of interference, change is also hindered by ideological constructs in the form of metaphors that reinforce 'business as usual' paths.

A consequence is that the short-term economic interests of a small minority outweigh the social, economic and ecological interests of the majority. Governments ignore the precautionary principle because it requires electorally difficult decisions. They avoid decision-making by starting one investigation after the other and shift the burden to others (Europe, provinces, municipalities, schools, the family, the individual). This postponing of actions burdens the future of young people, but they are not electorally important.

As a result, democracy has become less direct and less just. Administrations originally intended to represent and protect citizens and national interests, but this is less and less so. On the contrary, citizens are seen as difficult, fraudulent and only suitable for consumption. Not the common good but the interests of political supporters are central. A logical consequence is the increasing distrust in politics, whereby more and more people are wondering whether political parties can serve their interests. People withdraw into a comfortable private sphere or are attracted by authoritarian false certainties. This plays into the plans of populist movements that are opposed to 'the elite' and 'the system'. This makes sense, because politics is less and less a reflection of the hopes and needs of society.

Another flaw in the party-political system is visible through the increasing complexity of the current issues. These must be resolved by political parties with resources and procedures that were perhaps sufficient in the 19th century, but certainly are not anymore today. Everything has become interdisciplinary, but we still want to solve issues mainly through individual specialisms. All government departments depend on each other, but are largely managed as if they were autonomous authorities. All important topics have become general issues. We can see agriculture, healthcare, economy, climate, infrastructure, housing, spatial planning, nature, migration, developmental cooperation, social affairs, education, domestic affairs, defense, foreign affairs and finances interrelating in every important subject. A discussion about the future of Tata Steel without the European context, or without attention to healthcare, and a range of other aspects is by definition insufficient. Basically, issues must be managed as interdependent and complex wholes and not in isolation. That is only possible if they are managed from an integral perspective on social, intergenerational, international and inter-species justice and a clear vision on the world in which we want to live.

The paradox here is that the power of the conventional order is getting stronger and at the same time less and less able to solve our problems. Therefore, countervailing powers are needed. For those to emerge it is necessary to grow a culture of democratic citizenship and civic responsibility in which people collaborate to bring about a peaceful revolution of the democratic system. Our future depends on it.

Radicalize democracy

Our current democratic system cannot respond well to the issues that the polycrisis entails. We must ensure that the connection between scientific insights and a widely supported vision of justice will determine decision-making. The current representative democratic system will not do that. Fortunately, there is an alternative to party politics: decision-making that is done in a knowledge-driven, deliberative and direct democracy. For that we need to radicalize democracy. This means that the influence of party-politics is minimized and politics becomes a verb: an activity that everyone contributes to. This implies decision-making by rational argumentation aimed at practical solutions that take into account as many perspectives, connections, and complexity as possible. To achieve that, two things are needed. Firstly, more awareness about the urgency of systems change and secondly the development of a politics as active citizenship that puts an end to the outdated paradigm of state power through party-politics. In other words: a revolution in which power will start from The Demos, the people.

An important means of radicalizing democracy are citizens’ assemblies with representative participation based on sortition. These can make effective policy for complex problems such as the polycrisis [5]. This is because citizens’ assemblies make choices by a well-facilitated process and after extensive knowledge sharing and deliberation about the consequences for social, intergenerational, international and inter-species justice. They make policy based on their weathered knowledge about the subject, taking into account as many perspectives as possible and validating these on effectiveness and feasibility. And they can do that well because they do not have to take electoral considerations into account and are protected from the pressure of lobbyists.

Citizens’ assemblies can test their policy intentions for support through popular consultations. That ensures a good public debate on the subject under consideration. The initiative for such policies can also come from citizens themselves. In this way communities make political decisions. In addition, the representatives chosen by our current system must implement them. National legislation and local regulations are then largely established through (national, regional and local) citizens’ assemblies. The chosen representatives convert the choices from the citizens’ assemblies into formal policy and focus primarily on their implementation and on enforcing compliance. As this culture of direct deliberative democracy grows, efficient digital tools can support the process as Taiwan proved with several far-reaching political choices inspired by citizens’ assemblies in the period after the occupation of parliament by the Sunflower Movement [6].

Scene from the Allegory of Good Government (1338) by Ambrogio Lorenzetti, one of a series of frescoes in the town hall of Siena (Italy), to remind the magistrates of just how much was at stake as they made their decisions.

The themes that citizens’ assemblies decide about are grounded in the needs and concerns of local communities. In a deliberative system, communities will work out relevant themes per neighborhood, city quarter, and village and execute decisions within their own control where possible. There are already many examples of citizens’ cooperatives that are self-governing for themes such as care, well-being, housing, energy and food, increasingly with co-financing from the municipality. Themes where the interests can get larger than a village or neighborhood can handle, or where the opinions in the community differ in such a way that they cannot simply reach consent to choices, are treated by a municipality citizens’ assembly. This pattern can repeat bottom-up through the municipality and region into national and international choices.

This radicalization of democracy will meet resistance from the current system. It will be hard to move political parties to give up their power monopolies. Almost all attempts at democratic renewal in the past 30 years have been successfully neutralized. The Minister of the Interior in The Netherlands for example, recently announced that the lobby register, a device to increase transparency around corporate capture, will not come through. This as a consequence of an exchange between the liberal VVD and the reformist NSC: VVD wants to support a key political demand from NSC, the installation of a constitutional court, on the condition that NSC drops the lobby register. As a result, continued and unhindered political influence from corporate interests is guaranteed for the coming period. These examples, though offering compelling arguments for transferring the power of political parties to citizens’ assemblies, are also making it increasingly difficult to change the system from the inside out.

Given the increasing chances and the high risk of natural, economic and social collapse as a result of the polycrisis, we cannot waste time. The existing system will not change itself and it cannot be changed from the inside out. An urgent transformation of the democratic system is needed of a scale that in the past only succeeded sustainably in conjunction with peaceful civil resistance. Massively disrupting protests, where current politics hinders the self-governance of communities, seems to be the best way to make the changes to the system that are needed. That starts with furthering our awareness about the outrageous failure of party politics when it comes to social, intergenerational, international and inter-species justice. This also includes a shift of consciousness of thinking about power as based in an abstract political system and institutions, to a consciousness of power as grounded in love and care for each other and our communities and based on shared needs and values. That is the sort of power that drives the self-governance and cooperation of people and that, combined with the energy generated by the rage about the failure of our politics, can power a peaceful revolution.

Our current democratic system does not solve our most pressing problems but actually makes them worse. This leads to an unlivable world. We must transform the democratic system to be able to respond adequately to our major issues. A way forward can be found in deliberative and direct democracy rooted in community based self-governance, powered by love and care, grounded on the values and needs of our communities and perpetuated in citizens’ assemblies. This affords adequate decision-making for the complex issues of our time. In this way we can still prevent the worst consequences of the polycrisis and pass a livable world on to our children.

Sources

[1] Finnerty, S., Piazza, J., & Levine, M. (2025). Climate Futures: Scientists' Discourses on Collapse versus Transformation. British Journal of Social Psychology, 64(1), one12840. https://doi.org/10.1111/BJSO.12840

[2] https://www.pbl.nl/publicaties/klimaat-en-2024

[3] Kallis, G., Hickel, J., O'Neill, DW, Jackson, T., Victor, PA, Raworth, K., Schor, JB, Steinberger, JK, & Ürge-Vorsatz, D. (2025). Post-Growth: The Science of Wellbeing Within Planetary Boundaries. The Lancet Planetary Health, 9(1), E62 - E78. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2542-5196(24)00310-3

[4] https://www.esscr-net.org/resources/manifestations of-corporate-capture/

[5] Mellier, C., & Capstick, S. (2024). How Can Citizens' Assemblies Help Navigate the Systemic Transformations Required by the poly crisis. Center for Climate Change and Social Transformations. https://cast.ac.uk/wp-certent/uploads/2025/03/The-centre-for-climate-change-change-and-social-transformationss-cast-guidelines-how-citizens-assemblies-help-the-the-Systics-stem-stem-stem-stem-stem-stem-stem-stem-stem -stormsiss-transdationsss-transdationsss-transdavigss-transdestofss.

[6] see This interview with Audrey Tang, Digital Affairs Minister in Taiwan from 2016 to 2024